The Raven design is stabilized and they are in production at Spatial Audio Labs in Salt Lake City. Don Sachs lives in British Columbia in Canada, I live on the outskirts of Denver in Colorado, and we both communicate with Spatial on a regular basis.

Spatial Audio Raven Preamp

Spatial is supposed to be shipping the first "wave" from pre orders of this preamplifier in May, does anyone have one on order? Was hoping to hear about it from AXPONA but I guess they were not there. It's on my list for future possibilities. It seems to check all my boxes if I need a preamp.

Showing 50 responses by lynn_olson

I hope you folks like the Raven (which are built and sold by Spatial Audio Labs). It’s a miniature version of the power amp, with one stage of gain instead of three. It has both RCA and XLR inputs, with the balanced input going straight to the 6SN7 grids, and the RCA going through a studio-quality input transformer (which converts the signal to balanced). The volume control is a special-order Khozmo dual mono unit, with volume and L/R balance on the remote control. The output is also transformer coupled, with both RCA and XLR balanced outputs. Don Sach’s previous preamp had a special SRPP circuit, which used clever noise-cancellation techniques to reject power supply noise. The Raven similarly uses inherent circuit balance to also reject power supply noise ... although there isn’t much, since the power supply regulator itself has 130 dB of noise rejection. Probably the biggest sonic difference is the previous Don Sachs preamp used a cathode follower and a very high quality coupling cap in the final stage, while the Raven uses transformer coupling to accomplish the same thing. |

They are custom-design Cinemag, optimized for our circuit. They are not off-the-shelf parts, which have bandwidth problems with the output impedance of the 6SN7. The 6SN7 is one of the best tubes ever made, but is not easy to match with most transformers. That’s where Cinemag came in, who saw the 6SN7 as a fun challenge. Several prototypes later (design, computer model, build, measure, listen, and repeat the cycle), we arrived at the production models we’re using now. The Khozmo volume control is also optimized for this preamp, with a different signal path than most preamps. The Raven is balanced throughout, from input to source selector to volume control to vacuum tube to output. One nice thing about transformer coupled balanced construction is the risk of sending DC pulses to a delicate transistor power amp are greatly reduced. (Even when a transistor amp is switched off, a DC pulse of more than a few volts can damage the input transistors.) P.S. How does the output transformer protect a power amp? First, there’s a 4.5 times step-down ratio, reducing unwanted transients by a similar ratio. Second, the circuit itself is balanced, instead of a single-ended cathode follower exposed to a hundred volts or more. Circuit balance is typically 3% or better, reducing potential transients by a similar amount (about 30 dB). Third, and most important, transformers can never pass DC, unless the windings themselves have failed. By contrast, capacitors may pass "leakage current" and gradually short out as they age (a well-known problem when restoring vintage electronics). |

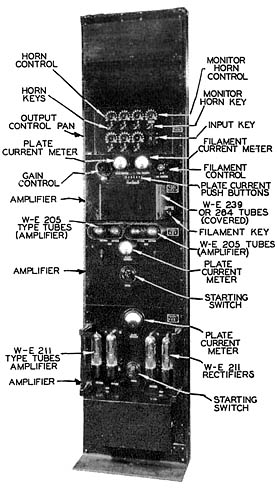

Yes, I’m curious too. Oddly enough, even though I designed the Raven in 1998, I never actually heard one until the Seattle show last June 2023. Don and I agreed it was good to choose tubes that were (A) in current production from respected vendors with an excellent track record of reliability, and (B) offer the option of using classic vintage tubes for folks who want to do that. So no unobtainium surplus tubes like 12SN7, ancient 101D’s, or using power-tube DHT’s in a preamp stage that require exotic anti-microphonic isolation systems. We want keep it simple and focus on the most linear circuit possible. The entire signal path is transformers, wire, and vacuum tubes, in a fully balanced configuration similar to Western Electric line amplifiers from the Thirties. It’s actually rather difficult to "tune" subjectively because there isn’t much you can tweak. One thing I can say: when you get rid of the last coupling cap in the circuit, surprises await. |

I started my career in audio with the invention, patenting, and prototyping of the Shadow Vector quadraphonic decoder, back in 1973. That SQ/stereo decoder was specifically designed to preserve ambient cues and spatial impression, without adding anything like a reverb circuit, or taking anything away from the source material. There’s a lot of content in a 2-channel recording that is destroyed on playback, or is below the threshold of audibility. This is not the fault of the recording, but the playback system. In general terms, this is low-level information with L/R phase angles between +/- 45 and 180 degrees. A (very good) quadraphonic decoder will route this information to the sides and rear, depending on phase angle, without affecting the frontal image or deforming it. Ideally, random-phase reverberation (from spaced mikes, reverb plate, or good digital reverb) should appear as an evenly weighted sphere around the listener, with no bumps, holes, or hotspots, just as it is in real, physical acoustic spaces. Again, this random-phase information is present on all stereo recordings with even a slight sense of space, because studio professionals consider "dry" vocals intolerable, so some reverb is added on just about everything. And the correct method of presentation is spherical, to match real acoustic spaces. Unfortunately, 2-speaker playback abbreviates the most realistic spatial presentation, although some speakers preserve a vestige of it. Smooth dispersion patterns, freedom from resonant energy storage in the drivers, and freedom from diffraction artifacts (no sharp cabinet edges) can allow the sound space to leave the confines of the speaker cabinet (as it should in a good loudspeaker). Most listeners never hear this, but it’s still there on the recording, waiting to be heard. (And no, it doesn’t take 11 speakers to preserve spatial information. That’s for special effects in movie theaters.) For some reason, electronics can also affect the spatial impression. I suspect that many electronics destroy, or alter, the low-level interchannel signals that convey this spatial impression, somewhat akin to MP3 lossy compression discarding "unnecessary" low-level bits. Nothing as violent as that happens in normal electronics, of course, but still, it subjectively sounds like bit reduction, with a loss or "air", spatial realism, and realistic tonality. I am not sure of the mechanism, but high-order nonlinearities, power supply switch-noise grunge, correlated noise, and odd, hard-to-pin-down capacitor colorations (possibly chemical reactions in the dielectric) all seem to play a role in shrinking the sound stage and destroying the ambient impression. That’s why the Raven and Blackbird minimize energy storage in the signal path. There are no feedback loops, either local or overall. There are no coupling caps, on the input, between stages, or on the output. The balanced circuit presents a nearly constant demand on the power supply, which is further smoothed by the shunt regulator tubes in the preamp. The signal goes in, is fed to a Class A balanced pair of very linear vacuum tubes, and is transformer re-balanced on the way out. No signal recirculation, no phase inverters, no cathode followers, and no secondary side chains (DC servo circuits, dynamic loads, etc.), even at very low levels (which is why it is so quiet). |

That's why I was pleased to collaborate with Don Sachs, starting a couple of years ago. I already owned his preamp, and I was quite impressed he had decades of experience on the insanely complex Citation I and Citation II preamp and power amps. Those products are not for the faint of heart ... Stu Hegeman was a seriously out-there guy, and a legend back in the Sixties. |

I expect to be there for the Oregon Triode Society demo as well. Maybe I’ll meet some old friends ... I joined the OTS way back in 1990 or so, at the second meeting. Way too far to drive all the way from the Denver metro area, so I’ll fly again, but take Business Class this time. My days of flying in Cattle Class are over, can’t handle the crowds or the itsy-bitsy seats the airlines use now. I do miss the Amtrack sleeper service from Denver to Portland ... that was a very nice train ride. Looking back, I look at the incredible complexity of that Shadow Vector patent (which I invented solo, unlike the three-person CBS team) and how I really jumped in at the deep end of the pool when I joined the hifi biz professionally. Working as a commissioned salesman was such a horrific experience I was strongly motivated to get out of Los Angeles and move to Audionics in Portland, Oregon. Although I had my differences with Audionics, they did believe in me enough to hire me to build the prototype, which took two years of hard work. That stretch was one of the biggest pushes I’ve done, along with finally completing my Psychology degree a few years later. Speaker design was considerably easier. |

Hope you enjoy it! Don Sachs, Spatial Audio, and I are right at the beginning of the production curve, with the preamps a little ahead of the Blackbird power amps. The designs are finalized, stable, and several steps more advanced than what was shown at the Seattle Audio Festival last June. Both are quite different than other tube audio products that mostly date from late 1950's designs. They are a combination of Bell System/Western Electric line amplifiers and 21st Century computer-designed transformers and power supplies. |

There is a whole subculture of modding the classic Klipsch products ... Cornwall (probably the easiest to tame), La Scala, Belle Klipsch, and of course the Klipschorn. Look up "Klipsch Forums" and off you go. Classic Klipsch are famed for dynamics but the frequency response can be sort of uneven in the 1950’s manner. Aside from response irregularities, the quality of the factory crossover parts is kind of marginal. But there are at least two different vendors selling premade souped-up crossovers for each of the classic Klipsch models ... no soldering needed. The KHorn definitely requires corner placement in order for much bass below 60 Hz ... the corner of the room completes the horn mouth, expanding it several times. Some folks actually use false corners, which work fine, provided the false wall is reasonably rigid and doesn’t vibrate. |

I heard the powered ATC monitors at the last Rocky Mountain Audio Festival, and they were some of the best speakers at the show. The ATC midrange driver, in particular, is a legend in the speaker industry, and ATC did a really good job with the active crossover and the internal power amps. The Raven can easily power 20 to 50 feet of balanced cable with its 4.5:1 step-down output transformer, so it should be an excellent match for the ATC monitors. Studio-grade Mogami or Belden XLR cables should be quite good, but there’s Cardas, Dueland, or Anticables if you want to spend more. I would stay away from high-capacitance cables that look like garden hoses. Capacitance is not your friend when it comes to long cable runs. |

Yeah, stay away from the garden hoses and faux snakes, no matter what the reviewer says, or in what magazine. Simple is good, less capacitance per foot is better. The studios don’t use garden hoses or faux snakes, why should you? Many of the reviews of $5000 cables are using them as system-wide tone controls. Wrong approach. Cables just need to get out of the way, nothing more. If EQ belongs anywhere, it's in the speaker crossover, where it can do the most good. |

As Don mentioned, avoid the thick and crazy-expensive audiophile cables. You have to remember most audiophiles have noticeably colored transistor gear, and use aftermarket products like power conditioners and $5000+ cables to minimize glare, grain, and excessive HF output in their systems. The better approach is using low-coloration electronics and loudspeakers with a smooth response, especially above 2 kHz. The key spec in any cable, much more important than any other, is capacitance per foot (or meter). Capacitance should be well under 100 pF/foot, preferably much, much less. Inductance *does not* matter unless you are running an AM transmitter (those are RF cables). Inductance does not load down the preamp, but capacitance does, occasionally causing transient instability in a preamp with high feedback. The Raven has zero feedback, but solid-state preamps typically have very high amounts of feedback (40 dB or more), resulting in load sensitivity to the preamp/amplifier interconnect. The quality of the insulator (dielectric) in the cable also affects the sound, and Teflon is not necessarily the best. It’s the first choice for aerospace applications, and has exceptional DF and DF measurements, but in my experience, may not the best for audio. Various types of plastic all have their own colorations, and the process of fabricating the cable applies mechanical stress to the plastic, which changes its dielectric properties. The more complex the construction, the more complex the coloration, and the longer it takes to settle down (possibly never). Most of all, DO NOT TRUST the reviews you see in magazines or on the Internet. |

Part of the reason for the sonics (aside from the circuit) is the physical simplicity of the preamp. No circuit board is needed because there really isn’t that much to the audio signal path. Input selector -> balanced switched-resistor volume control -> balanced 6SN7 vacuum tube -> output transformer. That’s it. There are no coupling caps, no multi-transistor current sources with Zener-diode references, no muting relays with time-delay logic, and no DC-balance servo circuits ... so there’s no need for circuit boards to contain all these secondary functions. Just very short point-to-point wiring. The same is true of the Blackbird power amp, as well as the Raven. The audio path is surprisingly simple. |

I’ve been using damper diodes (from old TVs) since 1997. I’m frankly surprised why people are still using the audiophile favorites. Damper diodes have (much) quieter switching, have substantially higher peak current, and sound noticeably better. The only downside is they consume a lot of heater current and require 6.3V heaters. The majority of damper diodes also use unusual sockets, so they are not pin-interchangeable with the standard types. The parameter I care most about is smoothness of switching. This is hard to get right, with most vacuum diodes having sort of a Class AB switching region. This can be examined by using a scope probe with a 100X internal attenuator and a safety rating of 1kV or better, connected to the secondary of the power transformer. Voltages are very high, so great caution should be exercised while making the measurements. The worst diodes have a rough transition between 0 and 50 volts, with holes chewed out of the waveform (generic solid-state bridge). The OK quality ones are fairly smooth but the zero crossing region (measured at the power transformer secondary with special probes) is quite obvious, with small variations between the usual audiophile favorites (which is where the famous tone color comes from). The best diodes almost look like Class A triode, with very smooth transitions that are complementary. Only damper diodes do that. They also have peak current capability that is 2X to 5X higher than any standard 5V heater diode. With skill, snubber circuits tuned to the transformer, HEXFREDs and high-voltage Schottky’s can approach damper diodes in quietness, which makes them useful for power amps that have to handle a lot of power. Why the obsession with switching noise? It’s much easier to reduce noise at the source then attempt to filter it later. The harmonics from the 100/120 Hz switch noise sneaks past regulators, magnetically induces noise in nearby circuits, and radiates back out the power cable. Better to minimize it right at the source, which is a function of the transfer curve as the diode is switched on and off. At Spatial, we use a belt-and-suspenders approach to power supply design. We select the quietest diodes for the application, use CLC filtering as a pre-filter, then apply that to a precision regulator with 130 dB of noise rejection. The regulated output is then applied to a balanced audio circuit with another 35 dB of noise rejection (due to inherent balance). The servo circuit in the regulator has very little to do since the current draw from the audio circuit is very nearly constant, thanks again to the inherent balance of the audio circuit.

|

I should go into regulators and their sonics a little. Yes, regulators have "a sound". Regulators are amplifiers that feed amplifiers, with the difference the "amplifier" amplifies incoming audio, while a regulator amplifies a DC reference voltage. But it’s an amplifier nonetheless. Most "linear" type regulators use an internal servo feedback loop to maintain a steady output voltage ... a regulator basically simulates a perfect battery, using feedback to get as close as possible to the ideal. But ... that is an approximation, not the real thing. There are very slight delays responding to a change in current demand, and that is where coloration enter into the sound. Some audio amplifying circuits have a steady current demand on the supply, and others bounce up and down, following the audio signal. A single-ended audio amplifier, whether tube or transistor, will have a current demand that mirrors the audio. You could put a current sense probe on the supply rails and hear perfectly good music (along with some buzz). A Class AB amplifier, by contrast, will have quite distorted music on the power supply rails, because it is switching between (B) the upper device, (A) both devices at once, and (B) the lower device. This changes the efficiency of the output stage as the different operating modes change with the music. The switchover between modes can either be hard or soft, depending how the amplifier is biased and how the devices enter the AB cutoff region. When the load is a Class AB device (like an output stage or an opamp), great demands are placed on the regulator. If it is not a perfect regulator (instantaneous and distortionless), coloration enters the picture. This is why regulators sound different, because a nonlinear load (such as Class AB) then exposes nonlinearities in the regulator. A balanced Class A amplifier has the great advantage that the load looks pretty much like a resistor at all times, short of heavy clipping. By contrast, the load of a single-ended stage looks like the music it is playing, always varying, while Class AB is quite distorted thanks to a pair of devices switching on and off as the music goes through it. Only well-balanced Class A has a steady draw that doesn’t vary with the music, whether loud or soft, all the way down to zero. Unfortunately, opamps are limited in not being able to dissipate much heat due to the small package size. Very few opamps are designed to be used with heat sinks. So the only way to keep heat emission low is efficient Class AB output stages, relying on feedback to linearize the crossover region (opamps typically have very high feedback). Higher powered transistor and tube amps also use Class AB to keep heat emission to acceptable levels, at the expense of higher distortion in the Class AB transition region. The nonlinear load challenges the regulator design, and regulators for the output stage of transistor and tube power amps can be as large and heavy as the output stage they are powering. In effect, one amplifier driving another. This is why it is very rare for medium or high power transistor or tube amps to have regulated output stages. Usually they have a simple lowpass filter with no regulation, saving a great deal of cost and weight compared to the regulated alternative. With no regulation, the sound will always change, depending on the incoming voltage fluctuations, the AC waveshape, and the noise riding on top of the AC power. The rigorous solution is fully balanced Class A operation for every stage of amplification, not just one or two, and low-noise precision regulators for each of those stages. This keeps the workload of each regulator to a minimum, and the current draw on each regulator is constant regardless of audio signal. It also maximizes isolation between the AC power line and the incoming audio signal. The Raven also uses an isolation and phase splitting transformer for unbalanced RCA inputs, while balanced signals go straight to the 6SN7 tube grids. Regardless of the incoming signal, whether balanced or unbalanced, the stepped-resistor volume control and internal electronics are always in Class A balanced mode.

|

Both the preamp and power amp are so symmetric we have to take extra care during assembly to make sure the phase is correct at the output. Multi-color wire comes in handy here. For that matter, the circuit is so robust it still amplifies with one side non-functional. Distortion is higher, of course, so it’s another thing to be checked during assembly and test. Both phases need to be present and accounted for, polarity correct in every stage, and both channels pair-matched. |

The Raven accomplishes several things at once: 1) Moderate voltage amplification (from the 6SN7). 2) Substantial current multiplication (from the internal step-down transformer). 3) Signal conversion from either RCA or XLR to RCA, XLR, and headphone outputs. 4) Volume control via stepped resistor array, with L/R balance control on the remote control, as well as volume and input selection. 5) Signal conditioning, with removal of DC offsets *and* RFI interference, and breaking of ground loops between components (via transformer coupling). So it’s not just a preamp or passive volume control. These benefits extend to all types of power amplifiers ... Class A or Class AB transistor, Class D Mosfet or GanFET, or triode or pentode tube amplifiers. RFI break-in is the bane of modern hifi gear, since most homes are bathed in microwave signals from WiFi, Bluetooth, and RFI noise from multiple switching supplies in TVs, computers, various gizmos that use ARM processors, etc. etc. Just scraping off all this RFI cruft before it gets to an analog circuit can make quite a difference in low-level sonics ... no more barely-audible buzz or hash getting into the power amplifier. The classic tube preamps of the Fifties and Sixties were designed at a time when nearly all homes were RF silent. No computers, WiFi, Bluetooth, or switching supplies. No wall-warts. None of that. The only RF-noisy places were TV studios (15.75 kHz TV sync buzz is everywhere), AM and FM transmitters, microwave relay towers, or military installations ... where isolation transformers were routinely used to isolate and suppress RFI incursion into audio signal paths. We are applying the same isolation technology used back then, with custom transformers that are designed with modern computer modeling software. |

RFI = Radio Frequency Interference EMI = Electromagnetic Interference (includes magnetic fields) 15.75 kHz (or close to it) is the horizontal scanning rate of 525/60 NTSC (color or monochrome) analog television. The 625/50 PAL or SECAM rates are similar. Analog television environments were notorious for high interference levels, as well as electrical noise from early SCR light dimmers for on-set illumination. Modern television is digital from camera, to signal processing, to transmission or storage, to decoding and display. No more sync noise, just computer hash at MHz frequencies. |

I own a Geshelli DAC and their new balanced headphone amplifier. Although value-priced, both products use the Sparkos (made in Colorado!) discrete op-amps, with a very large Class A operating region. If you’re going solid-state, this is an attractive approach. The Raven is kind of the opposite: Zero feedback, all-triode balanced, using some of the lowest distortion vacuum tubes ever made (6SN7). What makes it possible are the custom-designed input and output transformers ... before that, Don and I were limited to off-the-shelf transformers, which in turn limited the selection of vacuum tubes that would be compatible with the circuit. The original Raven, designed way back in 1998, used tubes in the 5687/7044 family. These are very good, but are not as linear as 6SN7 family, and the subjective difference is pretty noticeable. The zero feedback approach brutally exposes the sonics of every single part in the signal path, right down to the sonics of the volume control. Our custom transformers have outstanding sonics (subjectively), and a flat response to 30 kHz in-circuit. The Raven has a signal path of: a discrete-resistor volume control, wire, a balanced 6SN7 dual triode, and a custom output transformer. The unbalanced RCA inputs have their own custom input transformer for phase-splitting and ground isolation. Zero feedback vacuum tube circuits are not for everyone. If tubes make you nervous, I can recommend the Geshelli with Sparkos discrete op-amps (if the low price doesn’t offend you). If you are very price sensitive, there are lots of Shenzen-made products for $200 or less, with ESS converters and pretty decent op-amps. |

It might sound odd, but both the Geshelli and the Raven have a similar parts cost to retail price structure. Solid-state isn’t really that expensive if you buy the parts in hundreds to thousands quantities. And the expensive, heavy case with the 1/4" front panel adds nothing to the sonics ... that’s 100% marketing. Tube circuits, though, get expensive very fast. Top of the line transformers are NOT cheap. Precision regulated 300 to 450 volt supplies aren’t cheap either. Tubes, by themselves, are kind of mid-price, but again, the top-of-the-line models aren’t cheap either. Vacuum tubes have always been handmade, even in their heyday in the late Fifties. Same for transformers. None of this should be surprising. The majority of the solid-state market use parts that are made in quantities of hundreds of thousands to millions. This drives down costs. By contrast, the tube sector uses parts that are made in quantities of hundreds to a few thousand, several orders of magnitude smaller than the solid-state sector. |

I used to think that rules-of-thumb applied to transformers. Well, no. Maybe in the Fifties when they were designed with slide rules, but now you work closely with the designer and their simulation software, followed by a sample build. Model, build, put on the test bench, send the complete set to Don, he re-measures and auditions, and repeat as often as necessary. The Raven is now on the fifth version of the custom transformer set. As noted by Don, they are optimized for the 6SN7 in balanced mode and the most common range of loads presented by solid-state and vacuum tube power amplifiers. The secret of transformer-coupled audio design is a close working relationship with the transformer designer. In effect, the circuit is co-designed with the transformer designer. One of the great things about working with Don is he has good working relationships with key vendors, so we can get custom designs on a timely basis, and we know exactly how they were designed. This lets us further optimize our circuits around the custom parts, rather than work around an off-the-shelf part. |

The Raven has split windings on the output transformer so both RCA and XLR’s can be used at the same time (the RCA output uses one-half of the secondary winding). So feel free to use to use the RCA output to power the active subs. However ... the added cable capacitance on one-half of the winding, might, in principle, unbalance the XLR output a little bit. Maybe. Most likely not. Use low capacitance cable for the sub output, if possible. Mostly, try it and see. The Blackbird power amps have pretty good common-mode rejection, so unbalance gets washed out in the input stage. I keep hearing good things about the Rhythmik servo subwoofers, so you might check out getting a pair (using stereo bass, with the lowpass filter set to 40 Hz). Although horn speakers have gratifyingly low IM distortion, they drop off very fast below cutoff. It's basically a brickwall cutoff, so "pushing" them below cutoff has limited utility. |

The degree of overlap between the horns and the subs (at least two) will be entirely subjective. Unlike closed and vented boxes, horns do not have a smooth, predictable cutoff region (which is 12 dB/octave for all closed boxes, and 24 dB/octave for vented boxes). Instead, they drop like a stone, and the octave just above cutoff can be pretty rough as well. Combining the horn with the subwoofer will require judicious use of the "phase" control on the subwoofer plate amplifier, and messing around with the lowpass filter. The magic spot might be anywhere from 30 to 60 Hz. |

I should add that all folded bass horns are tricky beasts. They only exist because a true straight bass horn that is flat to, say, 35 Hz, would be the size of medium-sized car. In other words, the size of an adjacent room. Two needed for stereo, of course. PWK compromised with the real world by folding the horn (which creates internal reflections) and using the room corners to expand the size of the horn mouth. The internal reflections create ripples in the response above 150 Hz, and the cutoff region has +/- 5 dB ripples in the response, which interact with the room modes. This is why adding a subwoofer is kind of tricky. You have to integrate not two, but three things: the Khorn response in its cutoff region (which is definitely not flat), the built-in filter of the subwoofer amp, and the room modes. Having two (or more) subwoofers is very useful because the room modes for one subwoofer will be at different frequencies than the other subwoofer, which smoothes out both of them. It’s also why multiple small subwoofers, in widely spaced locations, is a much better choice than a single subwoofer. I should add the Khorn horn cutoff might be a lot higher than Klipsch says it is. 60~70 Hz would not surprise me. |

A pair of subs don’t need to be exotic or anything, just fill in the gap below the horn cutoff. And two are definitely better than one. I prefer stereo bass, but the home theater folks use a mono input to drive 2, 3, or 4. I don’t care about sound effects on movie soundtracks (who cares), but do care about wideband sound. One thing about the Blackbirds is they will tolerate absurdly reactive loads, since they are push-pull Class A and do not use feedback. No protection circuits are needed. |

Nice that the Raven ticks all the boxes! Seriously though, you’ve pinpointed (better than I could) what separates the Raven from a conventional Marantz 7C re-creation. The preamps from the Fifties and Sixties followed a pattern of 2-stage 12AX7’s for lots of gain, a 12AX7 or 12AU7 cathode follower to knock down the output impedance, and plenty of feedback around the whole thing. Look at an Audio Research SP-3A or SP-6 and you see the same circuit. This is what most audiophiles think is "tube sound" for the simple reason that hundreds of thousands of preamps and integrated amps were built just this way, so it’s a very familiar sound. But there are other ways to build a preamp, borrowing from studio electronics going back to the 1930’s. That’s the Raven, with no coupling caps, zero feedback, and a fully balanced circuit all the way through. More technically, when the Marantz (or similar) circuit is compared to the Raven, there are 1, 2, or 3 coupling caps in the signal path. "Tuning" the sound of a classical preamp is usually little more than a cap swap, leaving the circuit itself untouched. The classical preamp is single-ended, relying solely on feedback to get distortion down to acceptable levels. And the sonics of cathode followers remain controversial, depending on the nature of the cathode load (resistive, inductive, active current source, etc.). |

Links to the aforementioned articles: The Amity, Raven, and Karna Amplifiers These articles date back to 2004 or earlier, and some of my opinions have changed since then. The availability of custom transformers opened a broader palette of tube selections, and Don’s work on precision power supplies offered a wider range of possibilities in the overall design. I find it interesting that my objections to the sound of coupling caps is as strong now as it was back in 1997. Once you accustom to the sound of no coupling caps, adding them back in the signal chain is very noticeable. Much of what we expect of "tube sound" is nothing more than the sound of XYZ capacitors. |

I got whacked with Covid after going to the Seattle show last year. Both the Seattle and Denver airports were overcrowded zoos, so I’m pretty sure that’s where I got it. Fortunately, Paxlovid knocked it out in about 36 hours. This time, I will NOT fly Economy Class, will ask the airline for a wheelchair to traverse the miles-long concourses at Denver, and will wear a 95% filter mask until the A/C on the plane comes on. For older folks like me, the airports are an exhausting trek without some kind of assistance. They are not ADA compliant unless you tell the airline a day in advance. Otherwise, you walk, with no place to sit and rest. It’s unfortunate there are only two transportation options between the Pacific Northwest and Denver: a very tedious drive through the wastelands of southern Wyoming, or a United flight on a 100% booked 737 Max. Well, yes, I could rent a private jet, but that’s $20,000 per trip. Don’t think the IRS would accept that as a tax deduction. The most pleasant trip was taking the Amtrak with a private cabin, but that disappeared ten or fifteen years ago. Sure was nice, though, eating in the dining car while watching the West roll by. |

There is no headphone circuit in the Raven. There are different taps on the output transformer, like a tiny power amp, and the headphone output is simply a different turns ratio. You could use planar headphones with a 30 ohm impedance ... nothing would harmed ... but distortion would be higher than we would recommend, so we advise against it. But it would certainly work, music would play, nothing would overheat or crash, and no transistors or fuses would short out. The power supply would not care at all. All that happens is the tubes see a low impedance load, that’s all. Distortion goes up, not catastrophically, but a fair amount. So our advice to stick with 200 ohms or higher isn’t meant to scare anyone. This is not like connecting 1-ohm speakers to your favorite receiver and blowing the protection circuit, or taking out the output stage. There’s no protection circuit, there are no transistors at all in the signal path, and the 6SN7 is designed to operate with a watt or two on the plate. Unlike transistors, tubes like high temperatures, and don’t need heat sinks. All that happens with low impedance headphones is an increase in distortion, nothing else. It’s hard to convey just how simple the Raven is. The entire signal path is: input jacks -> input selector -> custom input transformer -> Khozmo balanced volume control -> 6SN7 in balanced mode -> custom output transformer with various output taps -> output jacks. There are no circuit boards in the audio path, all signal wiring is hand-soldered point-to-point. That’s also why the Raven has a medium price by high-end standards. There’s a lot of labor in every single part, most of all, the transformers, vacuum tubes, and final assembly. By contrast, a circuit board filled with op-amps inserted by pick-and-place robots would be about 1/10th to 1/20th the build cost of a Raven. That's why Shenzen-made products are so inexpensive ... op-amps are cheap, and robots can fill a circuit board in moments. |

Oh, Amtrak is still around, just with fewer routes. The Denver/Portland route went away about fifteen years ago. However, as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, Amtrak is getting some routes restored, which I look forward to. As for airports, DIA is truly gigantic, with six enormous concourses, all radiating from a rattly and jerky central subway. United changed the gate THREE TIMES on the trip to Seattle, all on very short notice. By the time I got my seat on the 100% full 737, I must have walked two miles, with no place to sit and rest, just a nonstop slog the whole way. Although I felt sorry for myself, I felt more sorry for the exhausted single moms carrying infants. This is gross violation of the ADA act. There are old people (me), folks on crutches, and single moms force-marched to distant gates through an immense facility with nowhere to sit. I think it’s absurd the wealthiest country on Earth has only two modes of transportation, with the airlines steadily degrading service year after year, and the Interstate Highway System no better than it was in the Seventies. Of course, if you are uber-rich, you just take your limo to the private-jet-only airport and stroll out of the limo straight onto the private jet a few feet away. |

300 ohms sounds about right. The output transformer is a step-down type, with ratios of 4.5:1 and 9:1. The previous Spatial preamp, the DS, uses a cathode follower instead of an output transformer. The output impedance is about the same, but a transformer multiplies current in proportion to the turns ratio, while a cathode follower has the same current availability as the tube ... which for a single 6SN7 section is around 8 mA (not much). The Raven multiplies that 8 mA * 9 = 72 mA, thanks to the transformer. If you have planar headphones with a 8 to 40 ohm impedance, a low power (and very very quiet) power amp is ideal. Only 1 or 2 watts are needed, and Class A operation is highly desirable. Something midway between the Raven and Blackbird, perhaps a two-stage integrated amplifier with DHT PP power tubes and about 3 watts of Class A output. Aside from headphones, the market for 2-3 watt amplifiers is pretty small. |

Well, our circuit is not an afterthought. The Raven is a small power amp, with no resistors in the signal path, but it is limited in scope to medium-impedance headphones. Supporting 8 to 40 ohm headphones would require a complete re-design and a substantial increase in price, with no sonic gain for use with power amps and loudspeakers. Our primary market are people using the Raven with power amps. The multiple taps of the Raven’s output transformer gives us the freedom to support medium-impedance headphones with no degradation in quality. No series resistors, no attenuation network, and no coupling caps, just a connection right from the transformer secondary. If we retain the same Class A balanced vacuum tube circuit, but scale it up to support low-impedance headphones, the price would end up midway between the current Raven and the Blackbird power amps. |

No adjustments are necessary. The only requirement is the sections within the 6SN7 are internally matched, which is true for any good-quality tube. Each channel has its own 6SN7, and it is preferable the stereo pair are matched, although not essential. (This is a roundabout way of saying don’t just use random pairs of old tubes pulled out of a junk box. The ones we ship with the Raven are the best modern tubes available. Before you try old-stock, make sure they are tested and known to be good.) |

Actually, I am very curious which phono preamps are a good match with the Raven. As mentioned earlier, the Raven sounds equally good with RCA or XLR inputs, so it caters to all kinds of phono preamps ... solid-state, vacuum tube, or hybrid. Not going to touch the "which streamer is best" discussion ... there are other fora that go into that rabbit hole. |

Hi, Theophile! I’ve written a lot of stuff over the last thirty years, both in print and many different Internet forums (going back to "rec.audio.high-end" in the days of the Arpanet). That’s when I was still at Tektronix in Beaverton, Oregon, and had access to lots of test equipment. One thing to note is the first capacitor in a classical CR or CLC supply is not actually a filter, and making this cap too large can create very large current pulses in the power supply, which then radiate out through the power cord and into adjacent equipment. Big transistor amps with more than 40,000 uF in the power supply are the worst offenders here. A bridge rectifier can "snubbed" to smooth out the worst of the current pulses, but the snubbing circuits must be tuned for the exact brand of power transformer. A mistuned snubber will actually make the ringing worse, so it’s not a one-size-all solution. As for pricing, Spatial is clearing a profit, but it’s not particularly large. Vacuum tube equipment is expensive to make compared to solid-state. Audio transformers are labor-intensive and the steels in the core are quite specialized and only made in small production runs. Vacuum tubes are not made by robots, but by experienced labor, in small production lots. Spatial uses hand-soldered point-to-point circuitry with exotic wire, instead of circuit boards, and switched-resistor volume controls are several times the price of conventional rotary controls. They are not made on a production line; one tech sits down and builds the whole thing, another checks his work, it goes on a burn-in rack, and gets thoroughly re-checked before final approval. By contrast, the most expensive part in solid-state gear is often the custom-machined front panel and case, followed by the power transformer. Transistors range from a few cents to a few dollars, and op-amps are rarely more than ten dollars each. Circuit boards are not that expensive if you buy them in lots of a hundred or more. So the actual working circuitry is surprisingly cheap, often less than 5% to 10% of the retail price. |

Kind of expected because: 1) the specialized damper diode rectifiers have very soft switching compared to solid-state diodes, thus much less 50/60 Hz switching noise radiated into the rest of the circuit and out the AC power cord 2) the regulated high voltage B+ power supplies have an astounding 130 dB of noise rejection from AC line noise 3) there is an another layer of VR-tube shunt regulation for the B+ power of each channel, good for about 20 to 30 dB of added isolation 4) All heaters are fed with 6.3 volts of regulated DC 5) last but not least, balanced operation of the 6SN7 circuit provides an additional 30 to 35 dB of noise and distortion rejection, without requiring feedback. That’s why the Raven (and Blackbird) cost a bit more than other preamps and power amps. Each Blackbird power amp does all this rigamarole three times, with KT88 and 300B power tubes, which is why it’s priced where it is. |

fthomsom251, you bring up a good point. When Don and I ditched the coupling capacitors, that pretty much got rid of the most obvious way of "tuning" the Raven. You see, nearly all coupling caps have a sound, one way or another. Get rid of them, there isn't much left to twiddle with. The interconnect might be about it. |

For better or worse, the Raven and Blackbird have high parts costs. Instead of a 1/4" thick sculpted aluminum faceplate (marketing!), we put the money into custom parts that are in the audio path. Pro-quality connectors, high-purity wire, custom transformers, custom Khozmo volume controls, and advanced linear power supplies all add up. Each one is handmade and hand-wired by Spatial Audio Labs. And the circuit itself, which doesn’t lend itself to a cost-reduced build. Instead of a lot of cheap parts (think opamps), there are a few pretty costly parts. If we had the same boutique styling and marketing expenses as other companies, the price would be double or triple what it is. |

We take for granted the very low prices of modern solid-state electronics. For a little perspective, look at the price of a RCA 21" color TV or Fisher FM/AM receiver in 1964. The cheapest color set was $500, and the receiver was $350. Wow, what a deal! Fire up the DeLorean! Well ... not really. Gold was $35/ounce back then. It trades for $2681/ounce as of tonight. You could get a decent house for $12,000 back then, and a really nice car for $3000. So that color TV with a 21" screen really cost about $5000 ... for the entry-level model. The floor model with a nice wood cabinet cost $8000. Or you could buy a 19" monochrome TV on a metal cart, with very poor picture quality, for $1800. That Fisher cost $3500, with the optional wood cabinet another $300. And no discounts either ... Fair Trade prices were enforced by the FDR-era Fair Trade Commission, not the free-for-all we have now. Quality tube electronics cost about the same now as then, which is no surprise because they are made the same way, with lots of hand labor by skilled assembly people. Cars likewise are complex and require lots of labor as well as capital investment, despite operating in a hyper-competitive world market. If what you want can be made with integrated circuits put on a circuit board with a pick-n-place machine, and the labor is minimal, you can have it at a price less than a tenth of what it cost back in the Golden Age. And I would take my 65" Sony 4K Q-OLED display over any 21" RCA television with a resolution lower than 330,000 dot triads. That’s a super deal by any standard. The value kings today are Class D amps with built-in streamers. Plug and play, the same as that 1964 Fisher receiver. Anything else is a luxury ... it’s up to you to find your happy medium. Personally, I find the tonality and subjective realism of transformer-coupled vacuum tubes to be unmatched by other technologies, but that’s just me. I got on that train back in the late Nineties with the Amity amplifier, and have been on it ever since. |

Any info on your power amps? Input sensitivity (volts RMS to clip the amp) and input impedance should tell the tale. Transistor amps (with feedback) are typically 1~2 volts to clip amp, and input impedance is typically 10K to 22K. The Bruno Putzey Class D modules are designed so they need they need about 10V drive and an input impedance of 6300 ohms. This non-standard input is intentional; it gives the third-party amp designer the freedom to design an input stage that has the tone color they want: op-amp, solid-state discrete, or vacuum tube. |

True. I surmise leaving the input section of the Bruno Putzey modules as they are was a deliberate design decision on Bruno’s part. The modules are an almost-complete power amp, but are incompatible with existing RCA and XLR interfaces, due to the low input impedance and medium-level voltage drive requirements. The OEM is then free to add as much or as little sonic flavor as they like. If they are catering to the ASR crowd, there are superb op-amps these days with truly exceptional measurements (they also sound good). If the OEM is up to a challenge, they can design a discrete transistor circuit, but it is very unlikely it will match the specs of the best modern op-amps. The days of the evil 741 and the mediocre 301 are long gone. The 5532/5532 is very old, dating back to 1979, but is still seen in pro gear. And if the OEM wants to earn the contempt of the ASR folks, they can use one or two vacuum tube stages, which will increase the distortion of the Putzey module a hundred or a thousand-fold. |

Yes, the requirements for the input/buffer stage are actually quite modest, not even a headphone amp, really. But the current fad for floating 12 or 15V supplies from a switching wall wart limits the output swing and current available. Barely enough for an op-amp (+/- 6 volts), plus losses from local sub-regulation. It makes sense for the op-amp (or discrete circuit) to be fully isolated from the Class D switching module. The Class D module generates program-modulated switch noise ... it's effectively a low-frequency AM transmitter contained within the chassis. That's where the efficiency comes from, after all ... when there's no program material, switching is still going on at 200~500 kHz, but no power is going through the output devices, and very little is drawn from the support circuits. There's no residual Class A idling as there is with Class AB amplifiers. The output devices are either on or off, with only extremely brief switch transitions. As program material level increases, more power and switch noise is created by the output switcher, and filtration demands on the speaker output and AC power supply increase. It is not trivial to silence a 200-watt AM transmitter in a can ... that energy is going to escape any way it can. Through the speaker wires (which make a great antenna), through the AC power cord, and even through the input jacks if it can find a way. Or leaks in the metal can itself. The adjacent linear audio equipment will have varying levels of tolerance for nearby RF emitters, which not usually tested in most test scenarios. Oddly enough, this is an argument for input filtration using transformers to prevent RF emission on nearby equipment. I doubt many will do this, though, since designers that use Class D modules also like the very low distortion of those modules. In the Class D world, distortion specs (and the respect of the ASR crowd) make a difference, |

So I doubt few, if any, designers of Class D amplifiers will use input transformers. The vast majority will use their favorite op-amp, or maybe try discrete op-amps designed for studio consoles. Boutique vendors that have a trademark "house sound" will design discrete transistor circuits that create the house sound. |

Hi Richard, that amplifier input load sounds very easy to drive. 1.5 volts to full clipping at 170 watts is very sensitive, and would require a quiet preamp. Any preamp, including ours, should drive it to ear-shattering levels. As for Ralph’s point about wall-warts, lots of DACs are powered by wall-warts these days. And lots of people use the DAC as the system volume control, since that’s a common feature of many DAC chips, such as the ubiquitous ESS Sabre chipset found in entry-level and uber-expensive flagship DACs. In an all-digital system, it’s up to the user if they want to use a separate preamp or not. In principle, a direct connection to the power amp from the DAC would have the cleanest sound. But in practice, it doesn’t always work out that way, and a dedicated linestage between the two sounds better. In that setup, the user disables the DACs volume control, so it runs at 100% output, and the preamp handles volume and signal selection. |